A PROCESS OF ILLUMINATION: Conversations about Erasure Poetry

by B.J. Best and C. Kubasta

If you google “erasure poetry” and click the Images button, you’ll find beautiful pages that are caught somewhere between occasional art and found poetry. When introducing poetry to non-poets, something that usually happens early in a semester in a creative writing classroom or introductory literature class, this can interest a student who worries that they don’t know where to start, or that they don’t have anything to say, or overcome the fear and dread that sometimes greets a not-yet-writer faced with a blank document. Erasure poetry exercises are a way to encourage playfulness with language, to introduce the idea that we write from the material that exists around us, that maybe writing isn’t some rarified activity of geniuses who hand down wisdom in ornate forms and perfect cadence. Also, sometimes when students encounter this strange way to begin writing they loosen up a bit, put their talents on the page in unorthodox ways. Last spring, in Kubasta’s class, students cut up poetry journals and research articles, like Pennycook’s “On the Reception and Detection of Pseudo-Profound Bullshit.” The result was erasure and collage poems like the below.

“This is My Title” by Abbey P (Erasure of Borman’s “Modern Form” with collaged quotations & mixed media)

Erasures can take many forms and serve many purposes. In addition to the freedom and creativity occasioned by this form, poet Isobel O’Hare notes the way this kind of writing can be considered an “act of uncovering, a sort of archaeology of language.” In describing erasure work this way, she argues that going after a printed page with a sharpie, or bottle of white-out, not only uncovers aspects of the source-text, but can also work to reveal what is hidden in the poet’s mind. O’Hare calls this a conversation—she talks about a variation of erasure where “I don't conceal the original words and allow them to sit beside the ones I've chosen to highlight, in greyed-out text.” She calls this “a process of illumination” that easily refers back to the image search of erasure poems. Some of them are decorated, or painted, and become artwork with words floating against backgrounds, landscapes original or generated through their own collaged processes. Another reason O’Hare cites for being drawn to erasure work is this idea of visual poetry; the arrangement of language in erasure becomes a kind of art. In choosing a source-text to work with, and a way of working, “The possibilities as far as materials are as expansive and unlimited as in any visual art form.”

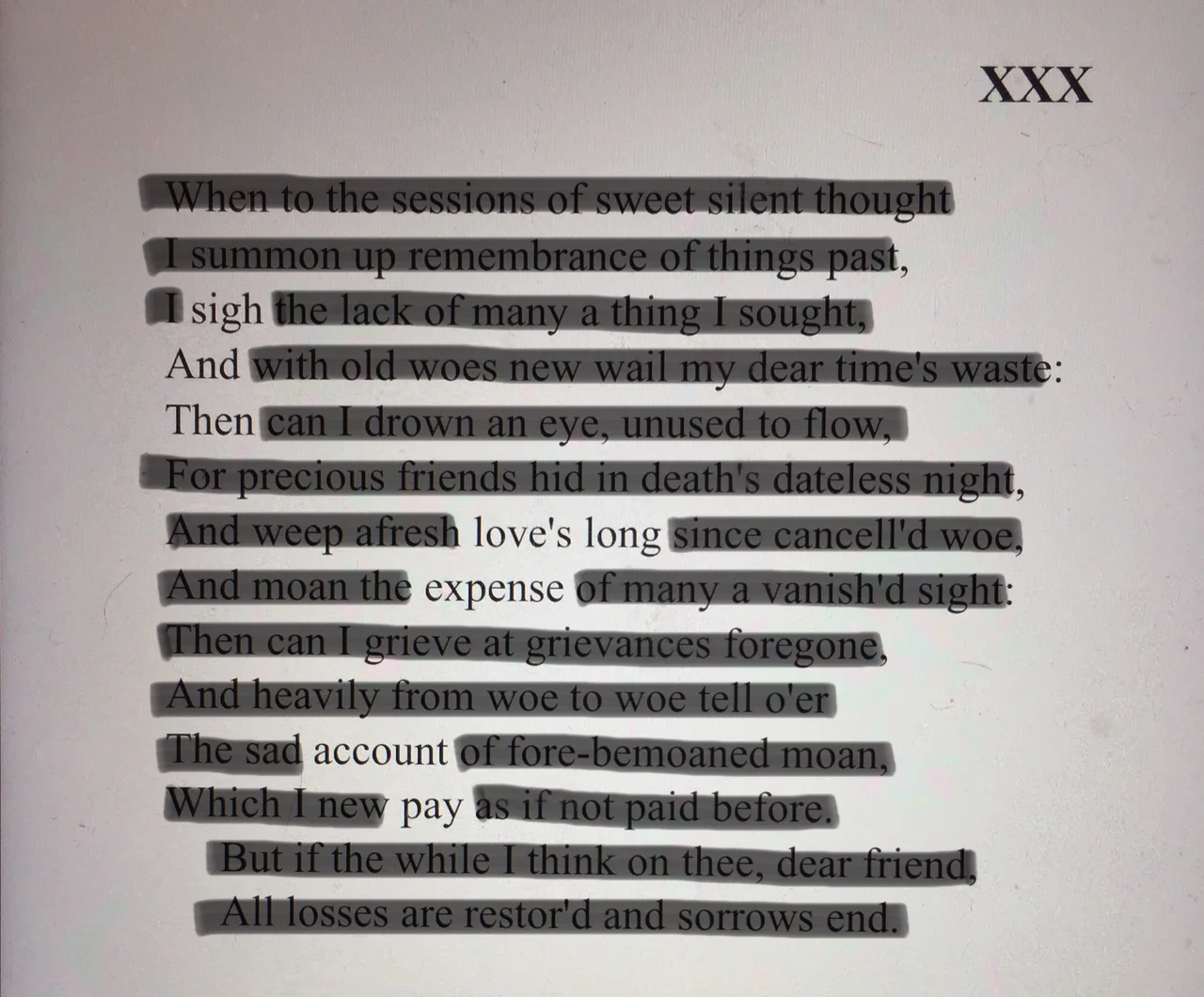

Ron Czerwein sees such possibilities as well. Recently, he has posted erasures of some of Shakespeare’s sonnets on his Facebook page. Like O’Hare, he grays out words from his sources rather than completely erasing them. He cites poet Jen Bervin, who has also created erasures of the Sonnets, and who uses white-out with “a thin enough coat that you can just make out the source text beneath.” But Czerwein’s considerations of these demi-erasures show how technology can influence their emergence:

My process was a little more convoluted. I took advantage of the edit feature in the photo app on my iPhone and iPad. I photographed each Sonnet on my iPad using my iPhone. Because they are stored in The Cloud, the photos appear on both devices. Then I use the marker function to “black-out” the text, leaving the poem. Only the black is more like gray and allows the reader to make out the text blacked out. This process also allowed me to work on the erasures from anywhere, as long as I had my device.

In this way, Czerwein relocates Shakespeare to a purely digital creation and distribution process, seemingly shifting the diction of Shakespeare’s poem into a thoroughly contemporary register. This temporal flux of erasures—rewriting words that were already written years or centuries ago—seems to be part of the form’s allure.

For Tori Grant Welhouse, that allure was directed toward an author with whom she was intimately familiar: herself. Grant Welhouse recently published two erasures in Two Hawks Quarterly, erasing herself from thirty years ago. She explains her choice to revisit her own work:

Two things converged, really. One, I passed my 50th birthday and was unaccountably heading towards 60, a birthday that felt rather monumental and was also prompting me to look back and reflect. Two, I reread this journal I kept as an MFA student in London. I was twenty-something, having one of life’s big adventures. The journal was both excruciatingly self-conscious and self-important. Yet there were some keenly-felt observations and the beginnings of poetic language. I started experimenting with erasure to see if it might help me bring to light these glimmers.

As Grant Welhouse notes, there is inherently a vein of experiment in creating an erasure as poets seek to mine the past to say something new about the present. In fact, she would create multiple erasures of the same poem to see a variety of possibilities, which “expanded my brain to see how the same page of words could create completely different works.” Erasurists seem to enjoy the strangeness and freedom from the typical constraints of writing a poem—Grant Welhouse mentions how much fun she had creating her erasures. Erasures are a form of linguistic play that pull on language in ways traditional poems might be unable to.

In addition to being playful, erasures can be overtly political, as Isobel O’Hare’s recent book All This Can Be Yours (University of Hell Press) demonstrates. In the wake of public accusations against powerful men, and the reckoning that came to follow, those men—or more properly their spokespeople or media handlers—often released statements about the accusations. When asked why she chose to work with these source texts, O’Hare notes:

Quite simply, because I found them so upsetting. As the apologies appeared online and I read them one after another, day after day, I felt rage. And erasure seemed the best outlet for those feelings, the best way to channel them safely for myself and for others. I also found the repetitive nature of them simultaneously fascinating and frustrating. One could teach a course on the history of misogyny and sexual assault using those apology statements as the texts. There were so many messages of "It was different back then" or "I remember the events differently" or "She didn't say no" or "I'm sorry she felt this way about what happened" or "This is a misunderstanding" or "This isn't who I am."

Czerwein, too, engages in the political; in fact, on Facebook he calls some of his erasures redactions, using the vocabulary of the Mueller Report and its elisions. Czerwein’s erasures “made reference either obliquely or directly to Trump,” such as the radical erasure of Sonnet 5, which remains only as “tyrants // walls // no.” In some ways, removing words from an existing text removes the agency from the original author and grants it anew to the author who is selecting the words for his own purposes.

In choosing a source-text to interact with, this might be a place to explore—pages that one already feels connected to, either through anger (as O’Hare did) or a personal connection (revisiting the self, as Grant Welhouse did), or with intent to provoke (“deface // some place / With // art, / Then [ ] depart,” as reads Czerwein’s redaction of Sonnet 6). Erasures can be a way of exploring a self in interaction with text, illuminating one’s reading, furthering an argument, or pushing that conversation out into the world.

O’Hare notes that there’s often a false dichotomy suggested, as if erasure poets aren’t creating “real poetry”—but she calls erasure a “form of constraint-based poetry.” It simply has its own rules, akin to nearly any other form. And as to whether erasures are creative or not, she mentions that whenever she gives a group of students the same source-text, they each come up with their own versions, finding their own poems in the text, their own voices. In particular, one advantage of erasure poetry is that the constraints of the form are often visible alongside the poem: something we at times cannot see with other set forms. Czerwein agrees and describes the generative possibilities of those constraints, saying, “I like the challenge of having to work within some prescribed set of limitations and trying to make something creative out of the materials at hand.”

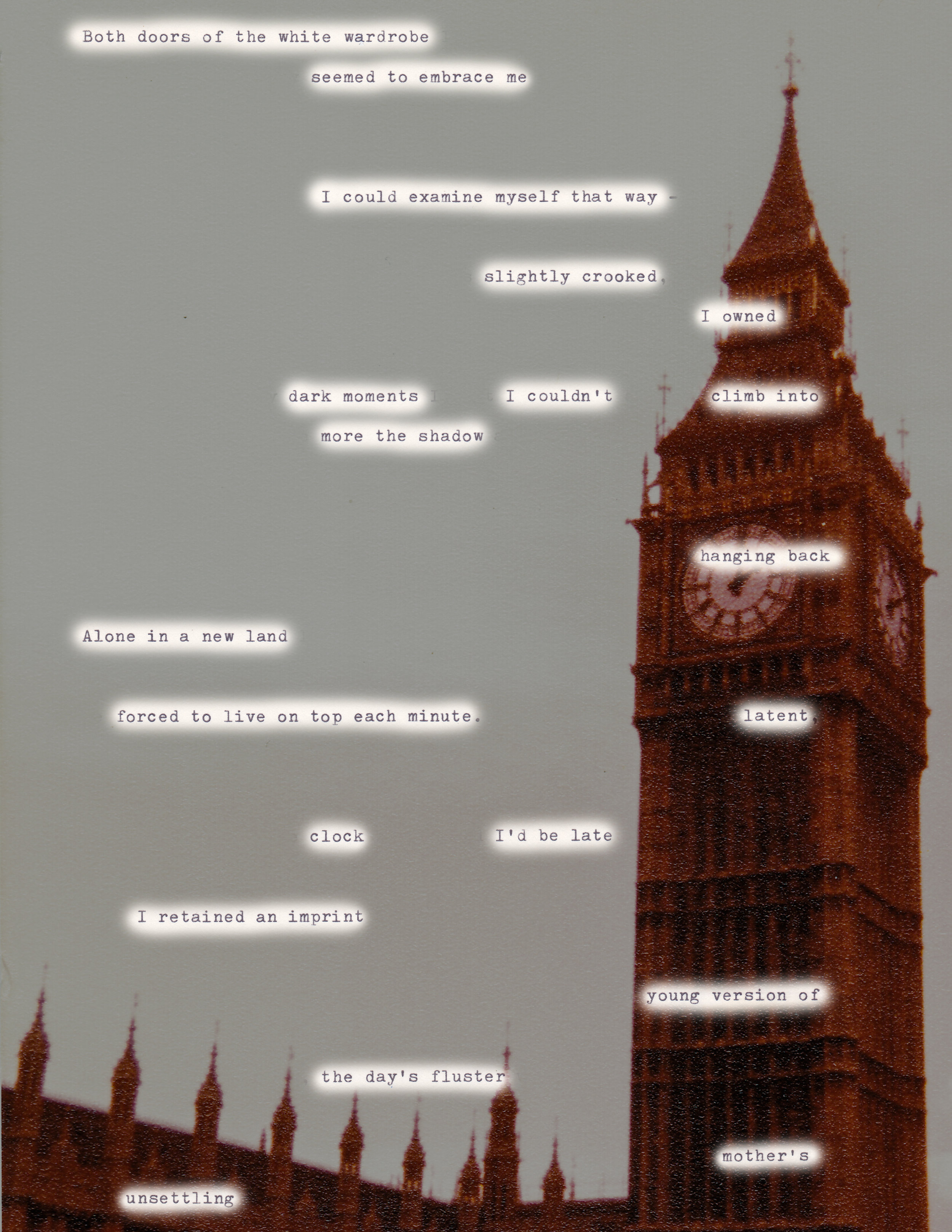

Of course, erasures go beyond simply eliminating words and instead put those words in the context of a visual image. “You are excising words to create meaning by word choice, word order, and spacing down the page,” Grant Welhouse says. In addition to spatial considerations, she also presents her erasures against a backdrop of photos she took while in London (which are also partially erased). The photos add another layer of meaning and context to her work, and help establish the London-ness of her younger self. She says:

I tried to pair photos based on chronology or theme, with the goal of adding dimension to the text. The photos were also aged and grainy, which I thought fit the mood of what I was trying to do. The erasures were definitely evoking a mindset of a place, which would have been harder to do without the images.

Visual presentation of a poem on a page is often left to the discretion of the publisher, not the poet, and erasures make us consider what can happen if a poet does not cede that artistic choice. A quick scroll through Google Images, as described before, or the Instagram feed of an account like @makeblackoutpoetry shows a variety of choices for the final visual presentation of a poem—from nearly all-black squares to wending mazes to whimsical illustrations.

There are so many ways to think of poetry, and writing, and voice, and it seems that erasure lends itself to a kind of metaphorical understanding. O’Hare offers a few more up, calling it “a form of divination or bibliomancy . . . Spending time uncovering these things in an erasure poem can be healing and illuminating, like giving yourself a Tarot reading.”

If the idea of erasures is interesting, below are some ideas. The (unfortunately) no-longer-publishing Found Poetry Review has some great information about Fair Use Guidelines when utilizing found material and source texts: http://www.foundpoetryreview.com/about-foundpoetry/

Part 1.

Choose a source text from another author—something that calls to you but not something you love so deeply that you’d prefer to leave it undisturbed—no longer than half a page. It needn’t be poetry: you could erase a newspaper article, a famous speech, a few paragraphs of a novel. Try making several different erasures of the same text. Try one version using a marker and paper; try another editing the words as a document or photo on a computer or other electronic device.

Part 2.

Choose a source text from yourself, much like Welhouse did. A failed poem, perhaps, or one written long ago. A journal entry would also serve well. Again, try multiple erasures and/or processes.

Part 3.

Setting the visual element of the erasure aside for the moment, reduce your preferred results from parts 1 and 2 to their words. Create a new poem by merging your two created texts. Each part could be its own stanza, or if you’re feeling adventurous, try alternating the lines or phrases down the page.

B.J. Best

B.J. Best is the guest editor of Bramble. He teaches at Carroll University in Waukesha, Wisconsin. His fifth chapbook, Everything about Breathing, is forthcoming in 2019 from Bent Paddle Press. Best has also written many children’s nonfiction titles through Cavendish Square Publishing.

C. Kubasta

C. Kubasta is the Managing Editor of Bramble. She teaches at Marian University, and her most recent books are the poetry collection Of Covenants (Whitepoint Press) and the novel This Business of the Flesh (Apprentice House). Find her at www.ckubasta.com and follow her @CKubastathePoet.